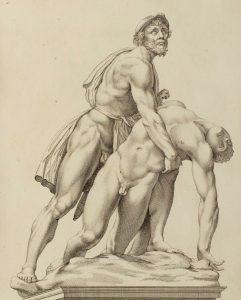

One of the iconic images from ancient times is that of two Greek heroes: Ajax holding the body of the slain Achilles. What ensued was a contest between Ajax and another great hero, Odysseus, as to which of them would inherit the armour of Achilles.

The remaining life of Ajax from this point is the subject of a book edited by David Stuttard that contains essays by a dozen Classical scholars, including Stuttard himself.

It was Odysseus who was triumphant in the quest to secure the armour, and it was his attitude toward Ajax in life and death that is central to the play Ajax written by Sophocles around the year 440 BCE. Studdard says at the outset that “most modern theatre goers will be unfamiliar with Sophocles’ Ajax, as only three productions of the play” have been staged worldwide from 2008 to 2018. Portions of the play have been staged during the past few years, as I discuss at the conclusion of this review.

Even though the play is ostensibly about Ajax, who was driven to a form of dementia by the goddess Athena because he refused her protection, it is Odysseus whose role is critically important. Even though they become enemies in life over the armour dispute, the reverse happens in death as Odysseus “learned to feel empathy for an enemy despite the fact that he (Ajax) fell into ruin because he did not properly respect the gods. Odysseus’ ability to see beyond even his patron god Athena shows that the potential for learning from a tragedy is such that it can go beyond any deliberate lesson originally intended by the play’s composer (Sophocles).”

In the play as stated by an author in this book, “Sophocles confounds the audience’s expectations by presenting an Odysseus who is surprisingly straightforward in his language, in contrast to the great deceiver of the Odyssey,” the iconic poem by Homer which predates Sophocles by several centuries. As two of the book’s authors point out, it is empathy that can be identified as the quality “that sets Odysseus apart in Ajax.” According to Homer in the Odyssey, the hero Ajax never becomes reconciled with Odysseus, even in death. But in the hands of Sophocles, Ajax is shown as a more nuanced character when he speaks the lines “I’ve learned just recently that an enemy should be treated as an enemy only in the knowledge that one day he might become a friend.”

As one of the authors in this book explains, “Sophocles takes a longstanding concern with the role of the great individual and how he should behave in his community, and explores it through a character (Ajax) who pushes his desire to maintain personal honour to the extreme.” In extremis, Achilles takes his own life by falling on a sword formerly owned by his great enemy Hector (lead warrior of the Trojans). Several authors in the book examine this scene in the play, which may very well have been enacted in full view of the Athenian audience, other suicides in Greek plays before this having taken place offstage and merely announced to the theatre goers.

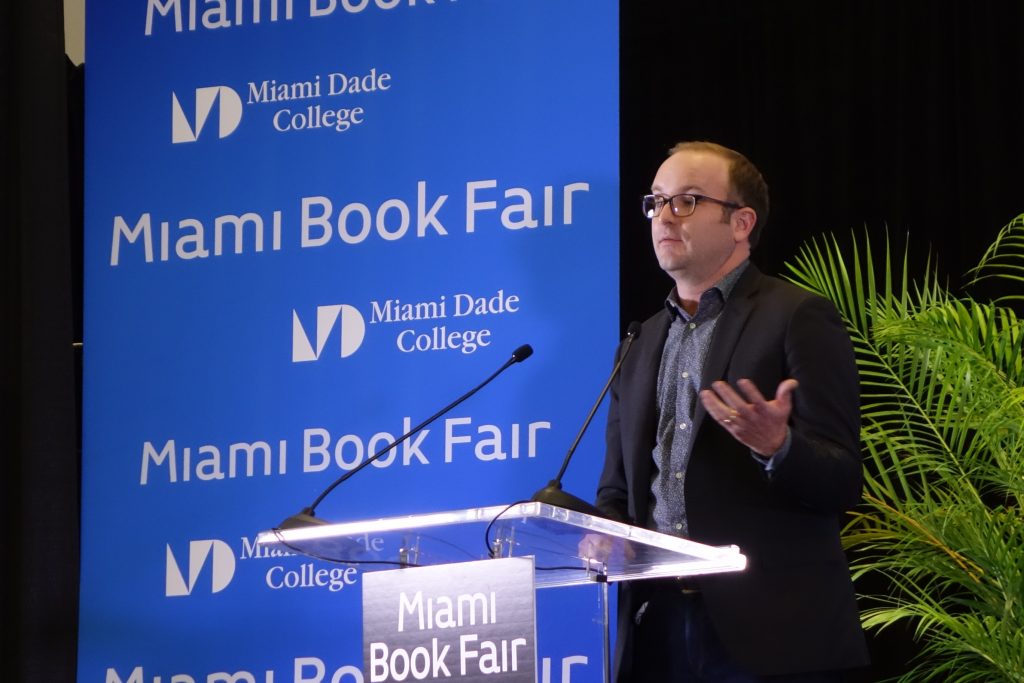

The final chapter is about how the decline of Ajax relates to modern post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the military. It includes a discussion of theatre director Bryan Doerries and his efforts to bring together audiences primarily from military families to engage with how Ajax can help them. I attended one of these performances, and a talk Doerries gave at the Miami Book Fair in 2015 (see my photo with this review).

Doerries does not directly link the term PTSD with his Theatre of War programmes (begun in 2009) that have been performed in many countries, referring to Ajax instead as “a fierce warrior who slips into a depression.” As noted by Sarah Cole in her chapter in this book, neither the staged performances and audience discussions afterwards by Doerries (or two other current projects that bring Ajax to modern audiences) substantially engage with the final 40 percent of Sophocles’ Ajax play. She strongly suggests these theatrical programmes should “seize the opportunity” to embrace the elements of the story after the death of Ajax, stating this portion “may be useful in bridging the gaps in understanding between ‘military’ and ‘non-military’ people brought about by the increasing social marginalization of the army.”

As the wife of Ajax states in the play, “There’s no greater evil for mortals than the stroke of inevitable destiny.” This book will appeal not just to those interested in ancient history, but actors and dramatists; philosophers and novelists who write about fate and the Gods; and those in the military of all nations who might ultimately have to face the same hard choices as the ancient Greeks. A concise book with 160 pages of text, and a complete new translation into English of the Ajax play which fills another 48 pages.

An interview with Doerries and two actors he works with on the Ajax project can be seen at this interview done at the 2015 Miami Book Fair by PBS:

https://www.pbs.org/video/book-view-now-bryan-doerries-interview-2015-miami-book-fair/

About the author:

David Stuttard is founder of the theatre company, Actors of Dionysus, translator of numerous Greek plays, and author of titles including AD 410, The Year That Shook Rome (2009), The Romans Who Shaped Britain (2012), A History of Ancient Greece in Fifty Lives (2014) and two other titles in this “Looking At” series by Bloomsbury: Looking at Lysistrata (2010) and Looking at Medea (2014).

Looking at Ajax is $97 by Bloomsbury Press. Website: Bloomsbury.com

Photo of Mr. Doerries by C. Cunningham; second illustration held by the Royal Academy of Arts, London