The Deco dandy has finally got the attention he deserves. While most of the focus on lifestyle and fashion in the 1920s has been on the feminine, the role of men in this transformative era has remained in the shadows in nearly every academic treatment. John Potvin, Professor of Art History at Concordia University (Montreal) has done a great service by rescuing the male aspect, specifically the one on display in Paris.

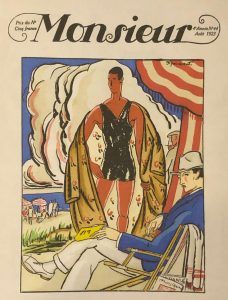

There was a fine line between deco and decadence in this era, and it was thoroughly chronicled by Monsieur magazine, whose articles and illustrations form the backbone of this important study. Virtually forgotten now, Monsieur was THE magazine for men in France, and even those in England and the Continent who could not read French must have been influenced by the imagery. It was Monsieur magazine that facilitated “the interpolation of the dandy into the narrative of civilisation through its critical writings on art, design and fashion.” It coaxed readers “to assume, embody and ‘become’ its content in order to create the ultimate work of art, that is, a fashionable and fit dandy.”

Each isssue had a unique colour cover, such as the one depicted here from August 1923, described by Potvin “as the new superman ideal visualized perfectly in the style moderne. Showing off his perfected physique, the standing figure is seen on the beach, with open billowing dressing gown which frames his body to best effect. The rounded contours of the gown reiterate the sculptural dimension of his deeply tanned musculature while its cape-like silhouette is a visual play on the newly emergent superman ideal advocated by Friedrich Nietzsche. The figure is also engaged in a dialogue with a (fully clothed) fashionably attired seated man. Both embody the corporal range that helped define the modern deco dandy.”

Potvin misses the opportunity to expound on the role of Nietzsche here, and it is the only mention of that philosopher in the book, but he also brings into play here Sigmund Freud, who argued that beauty formed an integral part of civilisation. The Classical ideal certainly influenced men’s fashion. Potvin includes illustrations from 1921, for example, which show a Classical nude figure in a sculptural pose, juxtaposed with the same man in top hat, white tie, and tails. Dandyism was largely about the clothes, and how the modern man should appear both in public and private. And sometimes the intersection of the two; who today, for example, would wear a dressing gown on the beach? A century later, times have changed.

Aside from general analysis, Potvin focuses in the book on three key “dissident queer figures: the expressionist painter Nils Dardel, silent film star Jaque Catelain and modern ballet dancer Jean Borlin. These three embodied “the ethos of lifestyle modernism” that ensured “life and art remained inseparable.” Potvin approaches all this in an academic way, asserting at the outset his aim is “about the conditions of consumption and the expressions of and theories and observations on dandyism to attempt a meta-perspective that both troubles and enlarges our current understanding of deco.” Comprehending this requires patience from the reader, who is not spoon-fed the usual pablum about gay men wallowing in decadence. It was serious for them, and he makes us understand that. “Consumed by the notion of the self as a work of art, the surface this implies on myriad levels reveals a depth that only fleshly embodiment can enable.” In this book, Potvin takes us on an exploration of those myriad levels, to reveal an existence hidden until now, even though it was in plain sight a century ago.

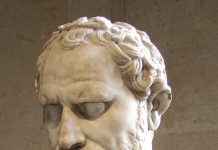

Nowhere was it in plain sight more than on the silver screen. Actor Jaque Catelain (1897-1965) was seen “as an alluring, seductive creature, the subject of countless swooning articles, speculation and photographs, decked out in the latest deco styles.” One of these is shown here, in a still promo image for his landmark movie Le Vertige of 1926. The electric effect he had on both men and women at the time leads Potvin to a justifiable excess when he writes of “Catelain’s frightening beauty.” One movie critic, in a review of Le Vertige, noted the female reaction as he made an entrance: “Suddenly all the girls shudder and undulate like wheat in the breeze. They are afraid to see Catelain enter. He is there, before their eyes, a modern Adonis.” Another critic wrote of him in another film, Le Figaro, asking “how one could not be astonished by the elegance” Catelain brought to the film? Dismissing such reactions is easy today, which is why the 20s has been so misunderstood by those who think they are experts on that inter-war era.

The other figures I mentioned, Dardel (1888-1943) and Borlin (1893-1930), had a working relationship that scandalized many, especially back home in Sweden (both men were Swedish). An article by a Swedish critic “alleged that the men of the ballet would surely be given a grand reception by the male prostitutes of Stockholm.” The author criticized how Borlin was portrayed as “a sort of Narcissus in skirt-like draperies; they are creations by none other than Dardel himself.” While he was a sensation in Paris, “Borlin’s effeminacy coupled with his increasingly avant-garde cultural production painted a picture of degeneration, decadence and national betrayal.”

Potvin sees a link between Borlin and art criticism in Monsieur magazine. “Not unlike Borlin’s ballet modern, which set into movement two-dimensional painted canvases, Monsieur’s critical interpretation of salon pictures sought to transform painted sartorial details in to the stuff of the dandy’s everyday lifestyle modernism.”

It really all came together in the film L’inhumaine in 1924. It starred Catelain, and “marks the first time modernist architecture was presented in a film.” The famous tailor Yose “proved to be ideally suited to Catelain’s character, a wardrobe worthy of the deco dandy. Finally, to round off the synergistic experience, on 4 October 1923 the Ballet Suedois (which Borlin performed in) provided the audience footage for the film. All of Paris was in attendance, 2,500 participants, including Man Ray, Picasso, Erik Satie, James Joyce and Ezra Pound. Wow! ‘Those were the days’ is truly not just an expression.

A truly important book about a critically formative period in modern times, this book is highly recommended.

There are two typos: on pg 27, “according Carlyle” should read “according to Carlyle.” On pg. 195 we see an image of Monsieur magazine from January 1921, but the text on page 194 states it is January 1920.

Deco Dandy: Designing Masculinity in 1920s Paris is 80 pounds by Univ. of Manchester Press.