Considering what is happening in the U.S. now, it might be a good time (even for those who are not religious) to read about Satan’s Second Coming.

The author of this title on the role of the Last Judgment in England of the 17th century is Ryan Hackenbracht, assistant professor of English at Texas Tech University. At its heart is nationalism, which for Milton and his contemporaries “was not only a horizontal affair between citizens but also a vertical one that pitted England against the shortly expected kingdom of God.” It is the vertical aspect that the author fingers as having been neglected by scholars. The scope of his remit in this book is ambitious. “The current book proposes to give a face to that religious influence, excavate its place in political imaginings, chart its points of contact with the nation, and trace the tension between them in period literature.”

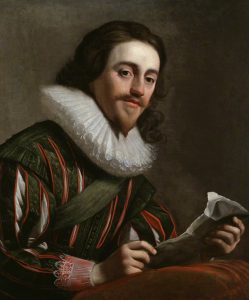

The “kingdom of God” referred to was none other than the Last Judgment. While it has still not happened, nearly 400 years after the period covered in this book, many people at the time expected it daily. The author describes it as “a cultural imaginary of inestimable influence,” something that was “both a near event on the horizon of history and a biblical narrative of comfort in times of political crisis.” Since political crisis was the order of the day in England in the 17th century, one expects people needed a lot of comfort. However comforting it may have been, the same people also had to contend with Satan’s Second Coming, a subject dealt with in chapter 5 as Hackenbracht writes on the trial of King Charles I. In the tendentious hands of Milton in Paradise Lost, Satan’s denial of his sentence from God “taps into the national memory of Charles’ trial” in 1648. Thus the title of this book, National Reckonings, is interpreted in terms of Milton’s epic. The argument is both convincing and chilling, but leavened by our knowledge that Milton was proved wrong when the true National reckoning happened: in 1660 the monarchy was restored. Milton should have been more wary of Oliver Cromwell and his morally bankrupt Commonwealth, who fooled Milton into thinking he was on the side of God. Little did Milton know he was being deceived by the devil he would so brilliantly write about in the 1660s.

Central to the argument about English nationalism is the role of Saul, first king of Israel. Here Thomas Hobbes and Milton locked horns. Hobbes, in his book Leviathan, declared “the kingdom of God is a civil kingdom.” Hackenbracht characterises this as “a bold statement, and it demonstrates his method of reworking scriptural narrative to extend the sovereign’s reach.” For Hobbes, every sovereign since Saul (including Charles I of England) is supreme in matters political and ecclesiastical. His account of Saul, writes the author, “appropriates a national rhetoric of revolution and turns it back against the revolutionaries.” Milton writes that Saul boasted he had performed the commandment of God, but Hackenbracht catches him in a lie: “Saul did nothing of the sort.”

The author captures the essence of the dichotomy inherent in these two great writers, whose influence was such as can hardly be imagined in today’s society. “For Milton, Saul is proof that monarchy is abhorrent to God and the English Revolution justified, while for Hobbes, Saul’s actions unshackled humanity from the chains of divine sovereignty.” Milton was not the only one on the opposing side. The author identifies Bishop Bramhall as his “most hostile critic,” but exposes him too as a hypocrite. “Despite his complaints that Hobbes is a poor exegete, Bramhall too was not above playing with scripture to endorse his own political views.”

Hackenbracht also looks closely at less well-known figures to give us a truly broad vision of what was a stake. The Cambridge Platonist Henry More, who hailed from Wales, “worked to antagonise the Commonwealth and frustrate its efforts to manipulate Welsh religion.” In a great poem, More writes of black parasites, code for black-clad officials from London. During the reign of Charles I, “these parliamentary parasites had been contained,” writes Hackenbracht. “Now, they bask in the warmth of the recent victory [against the King], and they swarm forth” over the Welsh countryside. More’s poem “uses reckoning as an engine of war against his enemies. Imagining himself among the martyrs in heaven, More wonders how the parliamentarians hope to tempt him.” Then he plays his ace card, invoking the Last Judgment, declaring the wicked would be cut down “when thy Master comes.”

Hackenbracht succeeds in placing before the eyes of a modern, secular society the motivating factors at work in 17th century England. By placing end-time prophecies such as Leviathan and Paradise Lost within their sociocultural surroundings, he reminds us of a time when the veil between justice on earth and justice in Heaven was gossamer thin. After Charles II was restored to the throne, John Gauden wrote a book entitled Cromwell’s Bloody Slaughter-House, wherein he “described God’s judgment upon the regicides as an end-time portent.” Gauden’s book “ushers that eschatological event into the historical present. The nation’s reckoning has begun.”

National Reckonings has 27 pages of notes, and a superb 21-page bibliography. It is not typo-free: on pg. 45, “to capture to” should be “capture the”; pg. 110 “broadening”, not “broadened”

National Reckonings: The Last Judgment and Literature in Milton’s England is $49.95 from Cornell University Press.