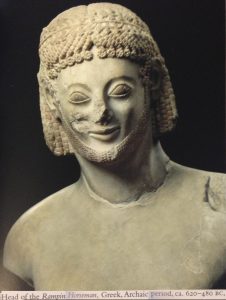

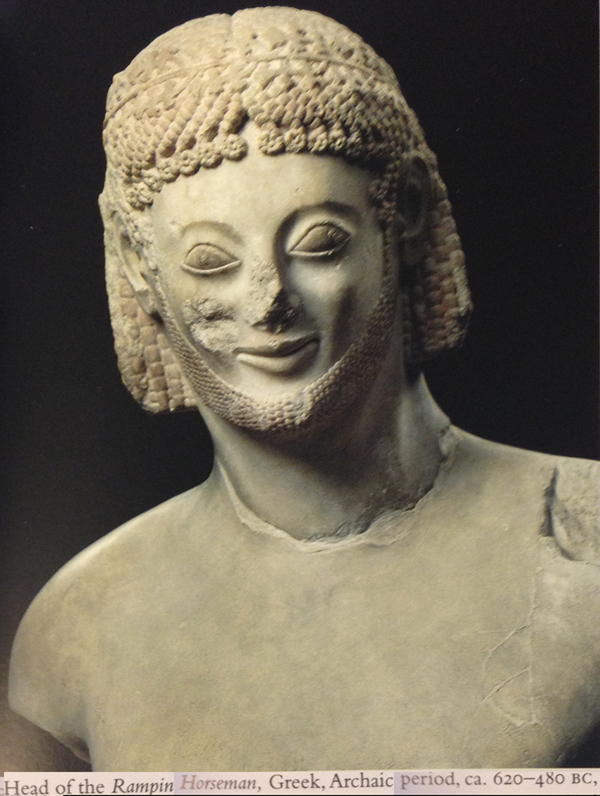

When one thinks of Ancient Greece, the mind goes at once to the so-called Classical Period, when Athens flourished, great philosophy was written, and democracy was born. But there were many centuries of Greek culture before that. Prior to the Classical period were the Dark Ages. And before those Greek dark ages was Archaic Greece, from 776 BCE (when the Olympic Games were founded) to 480 BCE ( when the second Persian invasion ravaged civilisation). This book looks at poetry during those three centuries of the Archaic period.

Dr. Jessica Romney at MacEwan University in Alberta, Canada, has written an insightful and invigorating poetic exploration that offers the first insight most people will have into this fascinating culture ruled by group identity. The poetry under consideration was a major element of that culture. “The texts flaunt themselves as more than a medium for the poet’s ideology, ideals and values,” states Romney. “They ask that we consider why archaic poets considered verse to be a useful method of communicating social and political values and ideas, along with the identities, groups and ideologies behind them.” These poems literally embodied the original beliefs of a collection of very exclusive cliques, giving us a unique insight into the rise of early Greek civilisation.

Fortunately for those who do not read archaic Greek, Romney offers an English translation of every passage. She lays the groundwork for her study at the outset, explaining the use of techniques from sociolinguistics to prise open the meaning of the poems. This branch of study “examines how language functions in social contexts and seeks to explain differences in language use, including how language use contributes to the negotiation and formation of social identities.” Combining this with an exploration of how discourse embeds social institutions, structures and ideologies, Romney assembles a fine toolkit with which to construct her thesis that identity as seen in archaic poetry “is a ‘process’ by which claims to sameness with others are established and sometimes contested. The recognition that identity is a process reveals the fiction of stability that identity claims for itself and those who hold it.”

Martial-themed poetry is central to her investigation, where a symposium (essentially an all-male dinner party) was the venue for these songs of battle. Martial lyric, she writes, enables everyone present to participate. Beauty, noble birth, and wealth – while important – all took second place over steadfast behaviour and the shield of war. A phalanx of soldiers could not be formed by aristocrats alone, so the martial lyrics spoken at the gatherings was a way to bring all into the group. The most famous poet of the age, Tyrtaeus, creates a dynamic balance between the elites in their full set of armour with those who have no such armour (called gumnetes, literally meaning ‘naked ones’). Addressing the young men of the gathering, he makes no distinction between them: “Come now! You who are of the line of unconquerable Herakles, take courage!” The poet promises the community will honour the “man good in war,” whether he is in armour in the front line or not. Such martial epic dates back to 700 BCE, but Romney writes it likely existed for a century or more before our earliest records. The Iliad and Odyssey (traditionally attributed to Homer) may date as far back as 800 BCE, and certainly informed the development of Martial lyric later in the Archaic period.

In addition to his exhortative elegies, Tyrtaeus also wrote Eunomia, a lengthy elegy on Spartan history. Romney is the first to suggest that the values proposed in his martial elegies “offered a preexisting military and political ideology to the citizens of Sparta,” thus placing the origin of that famous Spartan mindset further back in time. “Tyrtaeus’ poems would thus have been one of several strategies developed to perpetuate Spartan dominance.” Even though it may have resulted in a digression, I would have liked to see the author discuss the Eunomia and how it relates to Spartan culture more generally; as it is she merely mentions its existence (without stating it exists only in fragments), which leaves a reader not intimately versed in this matter unable to make the cross-fertilising connexions. This would naturally be somewhat speculative, given the paucity of the historical record about Tyrtaeus’ place in Sparta, but worthwhile nonetheless.

On a technical level, Romney teases out every nuance of the poetry of Tyrtaeus and Callinus, going line by line to show the reader how text of various grammatical forms address different people who are hearing the poems. The third person singular, for example, is directed at an individual (“let each man stand strong and remain”) while with the second person plural the poet “elevates to a higher position within the we-group,” telling them how to fight and more importantly, how not to fight. Finally, the first person plural is used to let “an audience see itself as a whole.” Callinus also used an exhortative strategy not seen elsewhere: the use of questions. He prods young men to rise up and be brave: “How long will you recline there? Are you not ashamed before those who live around to be so utterly relaxed?”

It must be noted that Romney gives us her own translations of the works of six poets. This differs from what you might read online. In some lines by Tyrtaeus, she writes “Rather let him go close to the hand-to-hand and let him seize an enemy, wounding him with his great spear or sword.” The translation on Wikipedia adds four words about actually killing the opponent: “But getting in close where fighting is hand to hand, inflicting a wound/With his long spear or his sword, taking the enemy’s life.” Overall I find Romney’s translation superior to earlier efforts.

Solon is certainly the most famous name from this period, but it is his poetry, not law-giving, that is treated here. In words that are especially pertinent in 2020, Solon wrote of a people who had lost their minds. “Yet the citizens themselves choose to destroy a great polis (City-state or country) in their recklessness, since they obey the unjust mind of the leaders.” Solon predicts these foolish citizens “will suffer much pain from their hubris.” We shall see in just a few weeks if the great polis of our time is destroyed by following the leader. The relevance of Archaic and Ancient Greece is eternal.

Complete with more than 50 pages of notes and bibliography, this is a thoroughly researched and utterly convincing explanation of the role of poetry in Archaic Greece. An important addition to any library dealing with military history, classical studies, and sociology.

Lyric Poetry and Social Identity in Archaic Greece is $75 from University of Michigan Press.