Are old people useless? Author Louise Aronson doesn’t think so, which is why she has written this book on elderhood.

Here is one way she sees old people are engaged: “Silicon Valley is scrambling to ‘capitalise on the silver economy,’ as the Economist magazine has phrased this booming business opportunity. From job search sites and ride-hailing apps to assistive robots and smart hearing aids, tech for older adults will not work unless designed with and refined through testing with older adults, which makes old people active participants in the tech economy.”

We are all old people in training, Aronson tells us, with life expectancy ever inching its way up. The branch of medicine known as gerontology is the oft-forgotten stepchild of medicine. The situation for the very old (the number of centenarians are increasing every year) is not helped by “learned helplessness:” this is the condition where most old people have the perception on how they should act

Each chapter of this well-written book contain bite-sized topics covering typically 2-10 pages each. This is very handy for quick reference to any of the plethora of topics the author covers. In one chapter, for example, we have such subheadings as Values, Truth, Biology, Advocacy and Outsourced. In the latter, we get a history lesson about homes for the elderly.

If you think old-age homes are a modern invention, think again. As usual, the Romans paved the way. Aronson tells us “a system of homes called gerocomeai was established, beginning in Constantinople. Rather than being tucked out of sight as inconsequential, residents were visited annually by the emperor in recognition of the potential political power of older adults.” In the Middle Ages monasteries took over the function of nursing homes, when these disappeared when King Henry VII abolished the monasteries. “Not until the Poor Laws centuries later did the British state again support local parishes in taking responsibility for their impoverished and elderly citizens,” writes Aronson.

She identifies “life satisfaction” as a key factor as an ever larger portion of the population becomes elderly. “Working longer,” she explains, “even if we work different jobs or fewer hours in our older years, is likely to increase our life satisfaction while decreasing our rates of chronic disease and disability; unlike disease treatments offered by medicine, it might move us toward true compression of morbidity- in other words, toward lives that are both longer and healthier.”

One of the many issues she highlights relates to prescription drugs. Often drugs are prescribed without consideration of age. For the old they may be harmful or ineffective. It is hard to determine as drug trials don’t use old people as test subjects. A related problem is when old people fail to tell their doctor of all the drugs they are taking: even a minor drug can have side effects.

Even when one does see a doctor, a real complaint is often dismissed in some fashion. The author tells the story (presumably true) about a patient complaining about knee pain. The doctor said “What do you expect? The knee is 95 years old!” To which the old man replied, “Yes, but so is the other one, and it doesn’t bother me a bit.” Apparently most doctors give a patient between 12 and 23 seconds to describe their problems, hardly enough for the aged.

Aaronson, whose is a medical doctor and professor of medicine at University of California, San Francisco, has produced a book that needs to be consulted by every care giver and health professional for the wisdom it contains. She states that “Life offers just two possibilities: die young or grow old.” If are old, or expect to get there, this hefty book of 449 pages should be on your reading list.

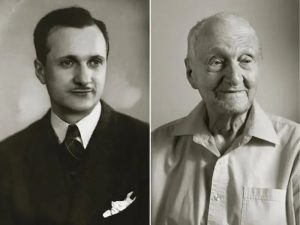

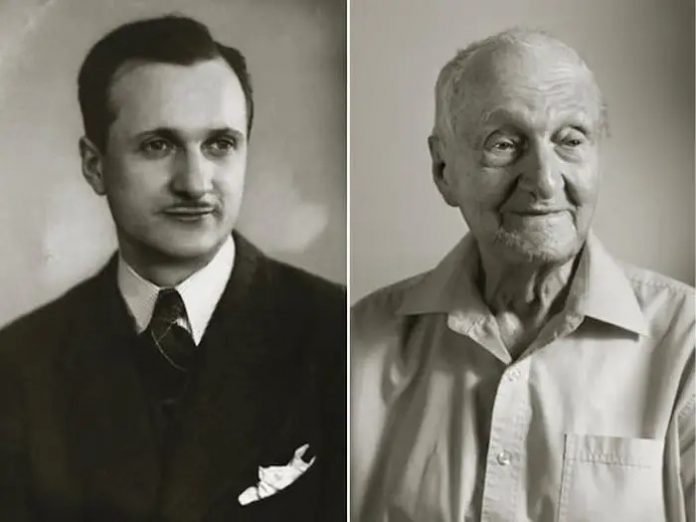

Photo of Antonin Kovar, at ages 25 and 102. By Jan Langer.

Elderhood: Redefining aging, transforming medicine, reimagining life; is $30 from Bloomsbury.

It has 403 pages of text, followed by notes, bibliography, and index. It contains no illustrations.

Review written by Dr. M. Emanuele & Dr. C. Cunningham