Please respond with a faith-filled “I do”.

Do you reject the academy? I do

And all of its works? I do

And all of its empty promises? I do

Excellent then. We can now explore together the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, who also rejected the academy; and, during the course of this review, I will also reject the Academy. Specifically, we are going to explore Nietzsche’s ideas on ethics. Now, Nietzsche is my favorite philosopher. Unfortunately for me, he had even less power of thought than Bertrand Russell, who had less power of thought than exactly nobody. However, Nietzsche had one of the greatest imaginations in the history of mankind and having power of imagination is much more important than having power of thought in my opinion. So, in the first part of this review, I will review why Nietzsche had no power of thought, and in the second part of the review, I will reveal how Nietzsche’s imagination can be put to use for the good of mankind.

Part I

This book on Nietzsche and Contemporary Ethics (written by Dr. Simon Robertson) seems to be particularly designed to disprove rationalists. Nietzsche of course was a sentimentalist and so took as his especial enemy Kant. This portion of the book focuses on Nietzsche’s overarching project of disproving that a universal and categorical morality exists. The most interesting parts of the book are chapters three, four, and eight. Of course, I do not have time nor do I desire to go over the entire book, which is 100 pages too long (the book is nearly four hundred pages). Robertson is a good enough thinker for a book that long, but he is not a good enough writer for a book that long. Chapter 3 takes as its subject the most basic challenges Nietzsche poses to the idea that there are universal and categorical moral laws. As everybody knows, Nietzsche particularly hated Christian morality, mostly because he didn’t understand it very well (at least in theory), but no matter, because I rather enjoy Nietzsche’s little account of how Christian morality came to be.

Here is what Nietzsche has to say about good and evil:

At first we called particular acts good or evil […] Soon, however, we forget the origin of these terms and imagine that the quality ‘good’ or ‘evil’ is inherent in the actions themselves […] then we assign the goodness or evil to the motives…We go even further and […] give it rather to the whole nature of a man […] the history of moral feelings is the history of an error.

Nietszche explained morality through saying that it was first created to protect communities against aggressive individuals who had once defended those very communities against outside threats. Once those outside threats seized to be threats, the community at large saw those aggressive individuals who had defended them as the new threat. Morality was conceived of to protect the community at large from those individuals who could potentially turn their aggression on the community. Furthermore, “the concepts good and bad were in turn used to draw and enforce socio-ethical distinctions of rank”. This meant that the powerful created the definition of values to control those below them. Nietzsche believed that Christianity was “a slave revolt in morals”. All of the milk-soppy Christian virtues were merely created to give peace of mind to people who were incapable of overthrowing their oppressors. Remember this narrative because I will return to it when I talk about Nietzsche’s imaginative power.

Let me turn to Nietzsche’s difficulty with Kant’s claims about categorical and universal morality because it is the most interesting part of the book, and it is also the kernel of the entire project of the book (and Nietzsche’s project of disproving categorical and universal morality). Kant said that laws apply to everyone and that human beings are capable of doing what is purely rational; human beings can cleanse themselves of their own motives in their search for what is purely and rationally moral. He also said that the concept of moral duty was implicated with the idea of a practical law applying to everyone. In other words, there are moral duties. “Doing what is rational to do irrespective of one’s subjective motives involves acting according to a law that could apply to everyone whatever their subjective motives.” From that last statement and several before it, Kant derived the Categorical Imperative: “I ought never to act except in such a way that I can also will that my maxim should become a universal law”. Nietzsche does not agree with this. He thinks that the belief that one should always act “this way” in a certain situation inhibits the autonomous creation of one’s self.

One should take into account one’s own interests. Indeed, Nietzsche would say that everybody should create his own categorical imperative. So Nietzsche was offended by the idea that there are universal laws which imply one ought to act in a certain way every time and a certain situation irrespective of one’s own interests. He was also offended by the suggestion that human rationality is untainted by subjective motives (on which I agree with him, though proving that it is tainted by subjective motives does not disprove the idea that there is universal morality. People may believe all of the right things for all of the wrong reasons). Now, Nietzsche believed that morality was also in the service of a herd instinct. He believed that most human beings had an innate herd instinct which prevented them from creating themselves and becoming great. However, he believed there was a select group whom he called “higher types” who could realize “excellence” and “higher virtues”. Nietzsche agreed with Kant that agents can govern themselves through laws. He also agreed that laws could be normative and he thought that normative laws could be self-legislated. But Nietzsche didn’t believe that those normative laws, whether they were self-legislated or not, could be universal. For instance, he believed that higher types self-styled their own lives and self-legislated goals in law-like manners. “First, the goals [projects that lead to self-realization and self-creation]. . . .a higher type sets for herself function as laws.” Robertson might say that higher types experience their commitments as “practical necessities”. Therefore, higher types are governed by laws, which are both the realization of their goals and the realization of higher virtues. All higher types are governed by these laws. But the reason why Nietzsche says that laws are not universal is because not everybody can be a higher type. It is an interesting premise, but impossible to prove. Because Nietzsche would have to prove not only that not everybody can become a higher type, but that there is no potential for those who are not higher types to become higher types. This, I am convinced, he cannot do, so his (and Robertson’s) entire argument about Nietzschean higher types being proof that laws or even self-legislated laws cannot apply to everybody is nonsense. I do believe that everybody is a higher type and can realize higher virtues. Therefore, I believe that the true realization of the self is the self-realization and self-creation of one’s talents. This was first proposed by Yeshua of Nazareth in his parable on the talents. In Yeshua’s spirit, I would even suggest that true salvation lies within a universal way which is particularly realized by finding one’s own talents and using them. Before I dedicate the remaining review to Nietzsche’s imaginative powers, I will just say that chapter 8 is substantially devastating to any rationalist point of view. I, thank God, am not a rationalist, nor am I a sentimentalist (like Nietzsche). I am an Imaginist. (Sentimentalism is the belief that one’s motives and moralities are significantly pre-influenced by one’s already inculcated predispositions and preconceptions.). Chapter 8 exposes several philosophical arguments pro and contra sentimentalism. In the last sections though, it amasses a body of empirical evidence to show that one’s rationality is significantly influenced by one’s emotions. Much of the evidence I find persuasive, although Robertson does use neuroimaging studies which purport to show that areas of the brain associated with emotion light up during ethical thought and cognitive judgmental activities. Neuroscientists don’t even know how a rabbit’s brain functions; they don’t know what emotions are, they don’t know how thoughts form, they don’t know how ideas form, and they don’t have a damn clue what creativity is. It seems a bit early to be using anything out of neuroscience to back up significant philosophical and ethical claims. Furthermore, because a part of the brain is lighted during an activity indicates nothing of whether that brain function is significantly influencing or constitutive of that activity.

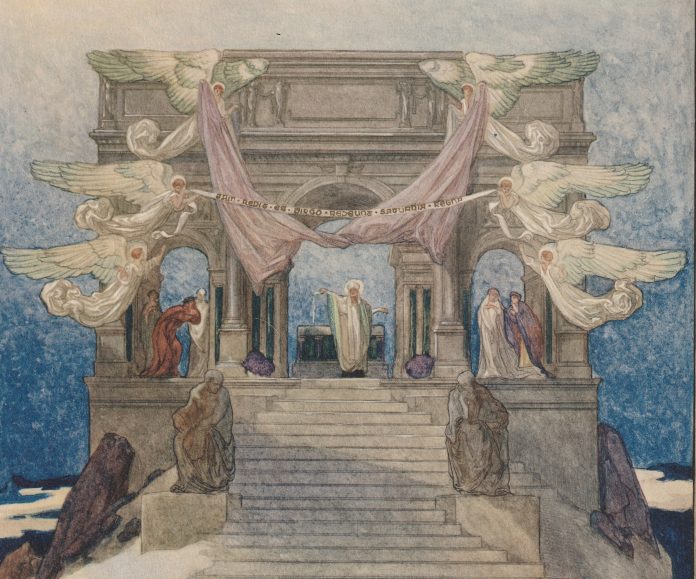

However, since I have no sympathy with rationalists and no sympathy with the idea that I or anybody else has pure rationalism, I applaud Robertson’s efforts empirically to debunk rationalism and its pretensions. Though, I always thought it would be interesting if reason itself walked about on its own two legs; what if reason itself (Logos) was a person, at least for a time? Indeed, what if morality or higher morality or whatever the hell morality you want to call morality walked around on its own two legs for a time? Then we could ask reason and morality itself what it constitutes and what constitutes it, could we not? I’ve always thought that asking Logos itself what constitutes morality is a much more attractive source for establishing any morality rather than making outlandish claims about how I or you or the neighbor next-door can rely on our pure rationality to derive pure morality.

I would suggest though that Nietzsche did not disprove Kant because he simply offered a competing vision to the vision of Kant (which Robertson assents to, but he says that the rationalist must offer the proof of burden for his claims); even Robertson’s attempt to prove that the goals which function as laws for Nietzschean higher types cannot be universal because the premise that not everyone can be a Nietzschean higher type is flawed. I have already said that Nietzsche cannot prove that everybody does not have the potentiality to be a higher type (nor do I think Robinson can, but the burden of proof is on him). I believe everyone may be a higher type: so I will derive a simple law (which finds an almost identical one in ch.3 of the book).

If one is a higher type, one always “ought” to realize higher virtues.

I think Nietzsche would agree with this. If everybody may be a higher type, than this law may be universal, in which case we are back to where we began. (In the case that you read the book, Robertson also presents arguments against Aristotle and Mill and each of their arguments for universal and categorical moralities. I think Nietzsche deals sufficiently well with Mill and perhaps even Aristotle; it is at Kant that he fails).

As a segue into my laudatory passage on Nietzsche’s creativity, remember that I said earlier that people may believe all of the right things for all of the wrong reasons. Now, Nietzsche knew quite well that in order to disapprove morality he really had to disprove God. You know all of the old arguments for morality that people who believe in God use. The problem with those arguments is that they’re very very hard to disprove if you cannot disprove God. Nietzsche was not a scientific atheist; he was not such a simpleton. He knew he could not kill God, even though he said that “we” had killed God (so far as I know, the only one not stupid enough to take him at his word is the wonderful Harold Bloom, who rightly saw that Nietzsche was a disciple of Shakespeare. Though if he was any disciple, he tried very hard to be Judas). Nietzsche’s Miltonically creative solution was to exile God. And I certainly believe that God is still in exile.

It remains today the greatest solution to destroying morality that anybody has ever created. It is a lasting testament to Nietzsche’s creativity. I admire Robertson’s dedication to Nietzsche, but I do not think any of his arguments against morality are essentially fruitful unless he can disprove God (and yes, the burden of proof is on Robertson because he set out on the Nietzschean project in the first place). I say that from a practical standpoint, not a religious or deistic one. The real reason I abandoned most academic philosophy because it goes about its business ignoring elephants in rooms and having no practical impact on the real world. And in that way, the Academy itself is anti-Nietzsche, who wanted his philosophy to be categorically practical. I suppose Robertson tries to have a practical impact in the second half of the book by developing “positive accounts of value and normativity”.

Chapter 10 is on flourishing as a human being. Robertson explicates self-understanding, self-mastery, and self-governance uniting to realize self-expression through agency as a Nietzschean definition of flourishing. There are many reasons to agree with some of it, but there are no reasons at all – nor does Robertson convincingly conceive of any – why these qualities are best understood by Nietzsche and why they are best realized within a Nietzschean worldview. Now, enough with Nietzsche’s broken attempt to disprove universal laws and prove positive accounts of normativity. I think Nietzsche has enormous use in the real world and I will now enumerate all of those uses.

Part II

Nietzsche had scriptural ambitions. He more than once attempted to re-write Pauline epistles: “The free spirit knows which ‘thou shalt’ he has obeyed, and also now what he can do, what he only now is permitted to do” is his attempt to re-imagine Paul’s admonishment that those who led by the Spirit are not led by the law. St. Paul again says that all things are lawful for him, but not all things are good for him (which Nietzsche, I am convinced, was always bothered by because it avoided his attack on morality in more ways than one). Thus Spake Zarathustra (which I try to return to every month) was Nietzsche’s answer to the Gospels and the Old Testament prophets of the Hebrew Bible. Everyday, I am more inclined to believe that Zarathustra was Yeshua reimagined in Nietzsche’s likeness. I think that Nietzsche’s scriptures have certain revelatory aspects: I myself have never read someone more comprehending of the modern world. (And by the way, Dr. Robertson, you are sixty years behind the times. Nobody really believes in Christian morality anymore, not even Christians. Nietzsche’s project (and yours) of rejecting universal morality has no relevance because Christian morality has been rejected by everyone save an ever-diminishing few. That is why one can sleep with three girls before the age of eighteen and nobody will give a damn. That is why all of my best friends can live openly as homosexuals without being arrested or censured by society. That is why some people pay a doctor to castrate them and so claim they are females, etc. . . . But, you’re an academic, so I forgive you for not realizing you are behind the times). I said before that Nietzsche understood the modern world: “Thus did I come to you, ye present-day men, and into the land of culture. . . .With fifty patches painted on faces and limbs—so sat ye there to mine astonishment, ye present-day men!” [TSZ XXXVI]. Nietzsche was terribly accurate in perceiving that the human vocation (which is to re-imagine all things for oneself) had been abandoned years ago or even centuries ago. People were no longer willing to re-imagine all things for themselves; they no longer were willing to engage their minds with every aspect of life. They were slowly made into herds (see A Thousand Ponds for Narcissus and Many Lack Human Identity) through the enlightenment deification of rationalism. Humanity, like the academy, sits gaping at the thoughts of other men, as vigorously opposed to originality as Mr. Robertson is opposed to universal morality [see TSZ XXXVIII].

Nietzsche’s vision of the birth of morality is more useful in explaining why the different identity herds now roaming our cultural landscape are so desperately afraid of any suggestion (in word or deed or even thought) of disagreement with their moralities. Indeed, the primitive societies of this society are afraid that individuals will turn their aggression on those primitive societies and destroy them. These societies have created moralities of their own to control their members and also those who are not their members. The gay group has its morality, and the straight group has theirs, and the black group has its morality. Nietzsche’s satirical and serious observation of people with painted faces has taken on subtle meanings: half of this country identifies with either the black face or the white face or some sort of painted face.

I find Nietzsche the most creatively compelling of all philosophers besides Augustine of Hippo; however, I know that Nietzsche loses his compelling aspect when he is translated into the dull and juridical idioms of contemporary (and so irrelevant) modern philosophy. I will continue to read Nietzsche and I suggest you do the same. Read him as he was meant to be read; interpret him creatively and not legally, like Dr. Robertson. Nietzsche pretended to be a philosopher, but he was really a poet. And I will always read him as such.

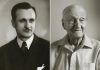

Simon Robertson completed a PhD at the University of St Andrews in 2005. He has worked at several universities in the UK, most recently Cardiff University (2012-18). His main research interests are in ethics, normativity, risk, and Nietzsche. He has published in each of these fields, in journals and edited collections, and is the editor of Spheres of Reasons (Oxford 2009) and coeditor with Christopher Janaway of Nietzsche, Naturalism, and Normativity (Oxford 2012). He is now an independent scholar.

Nietzsche and Contemporary Ethics is $90 from Oxford University Press.