Courtesy of the Bank of America, Tucson is now hosting a marvellous collection of paintings by America’s First Family of art: the Wyeths.

The Bank of America Collection is one of the largest and finest in the world, although its size and value have never been disclosed. The bank did not set out to collect art. Former CEO Hugh McColl Jr. liked to quip, “We just collected banks.” Still, many of those had art collections – Security Pacific National Bank in Los Angeles, Boatman’s Bancshares in St. Louis and FleetBoston Financial in Massachusetts. The BofA now loans its art at no charge to museums around the country: in this instance the Tucson Museum of Art.

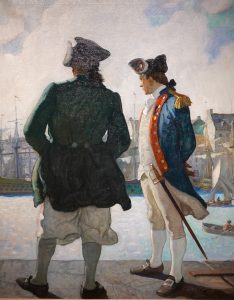

Fans of Wyeth family art have certainly viewed the foremost collection, on display in Rockland, Maine; I saw it in 2018. It includes many of the Revolutionary-era illustrations done by the patriarch of the family, N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945) in the 1920s. One not included there can be seen in Tucson, depicting John Paul Jones on a sea wall, gazing out at a crowded shipping scene. Like many of N.C.’s illustrations from this period in American history, it was created for a book. Many appeared in Poems of American Patriotism in 1922. Drums, written by James Boyd, was another such book. The hero of the story is Johnny Fraser, who is shown in the painting by N.C., although his back is turned to the viewer. The caption states Fraser “appears uncertain in comparison to Jones, who seems strong and resolute.”

Fans of Wyeth family art have certainly viewed the foremost collection, on display in Rockland, Maine; I saw it in 2018. It includes many of the Revolutionary-era illustrations done by the patriarch of the family, N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945) in the 1920s. One not included there can be seen in Tucson, depicting John Paul Jones on a sea wall, gazing out at a crowded shipping scene. Like many of N.C.’s illustrations from this period in American history, it was created for a book. Many appeared in Poems of American Patriotism in 1922. Drums, written by James Boyd, was another such book. The hero of the story is Johnny Fraser, who is shown in the painting by N.C., although his back is turned to the viewer. The caption states Fraser “appears uncertain in comparison to Jones, who seems strong and resolute.”

N.C.’s historical paintings for books extended far beyond American history. My favourite is on view here (a detail of the work is the lead photo with this article). It illustrates a scene from The White Company by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (most famous for his Sherlock Holmes books). The book is in a display case, so one can read the entire passage upon which it is based. “Here is Sir Nigel Loring, on foot and with his sword,” said the prince. “I have heard that he is a fine swordsman.” “The finest in your army, sire,” Chandos answered. The painting shows Sir Nigel, right, sustaining England’s honour against a mystery opponent.

There are many examples of the work of N.C,’s son, Andrew (1917-2009) and a few by his daughter Henriette (1907-1997) and her husband Peter Hurd. Andrew also drew inspiration from Revolutionary War times; the one shown here is of a Redcoat (British soldier), done in 1982. The caption states Andrew, as a boy, often wandered through the land that saw the battle of Brandywine. As an adult, he continued to collect toy soldiers. Henriette enjoyed painting flowers. “It reminds me of the eternally renewed, the springtime,” she wrote. The one shown here is entitled Nat’s Blue Shirt from 1984.

The current scion of the family, Jamie (born 1946), has taken the Wyeth family art in new directions. One on display is a full-length study of the ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev (who I saw in a performance of Romeo & Juliet). The one by Jamie shown here is Pumpkinhead Visits the Lighthouse from 2000. Here his persona as Pumpkinhead visits the artists’ home on Summer Island off the coast of Maine. The painting expresses that, like his father, Jamie prefers to be an unseen observer of the world around him.

Unfortunately, there is no catalogue for the exhibit, but the accompanying captions are excellent. Some of the books in which the paintings have appeared are on display, which certainly enhances our appreciation of them. Overall a beautifully mounted exhibit of some 60 works, and a great reason to visit the Tucson Museum of Art before the Wyeth paintings depart on May 9. If you are non-plussed by most of what has passed for ‘art’ in America in the past century, this exhibit is for you. This is real, this is art.