“Those who desert the constitutional position handed down to them by their ancestors, and whose political conduct is oligarchic, should be deprived of the civic right to offer you advice. It is those whom you know to have committed themselves to the enemies of our city in whom you put the greatest trust.”

What American statesman spoke those words laden with imminent doom? Was it perhaps said on the day when the President’s closest medical advisor, sitting in the White House, flirted with treason by speaking on Russian State Television about the President’s political rival? What statesman spoke out about the enemies of the state in that House of the people, in whom tens of millions have pledged their greatest trust by voting for four more years that will see the fall of democracy itself?

Sadly, America has no such great statesman who commands unrivalled respect (this is not to fault Mr. Biden, whose has an unblemished moral character and deserves the presidency; rather, it is a fact that no one has such auctoritas in such a divided country). The words were not spoken in this country or in this time, but they reveal an inherent truth about democracy, a truth that is inherent for the very reason that it derives directly from the dark side of human nature – a nature that has not changed for thousands of years.

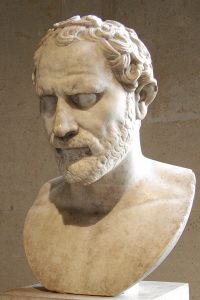

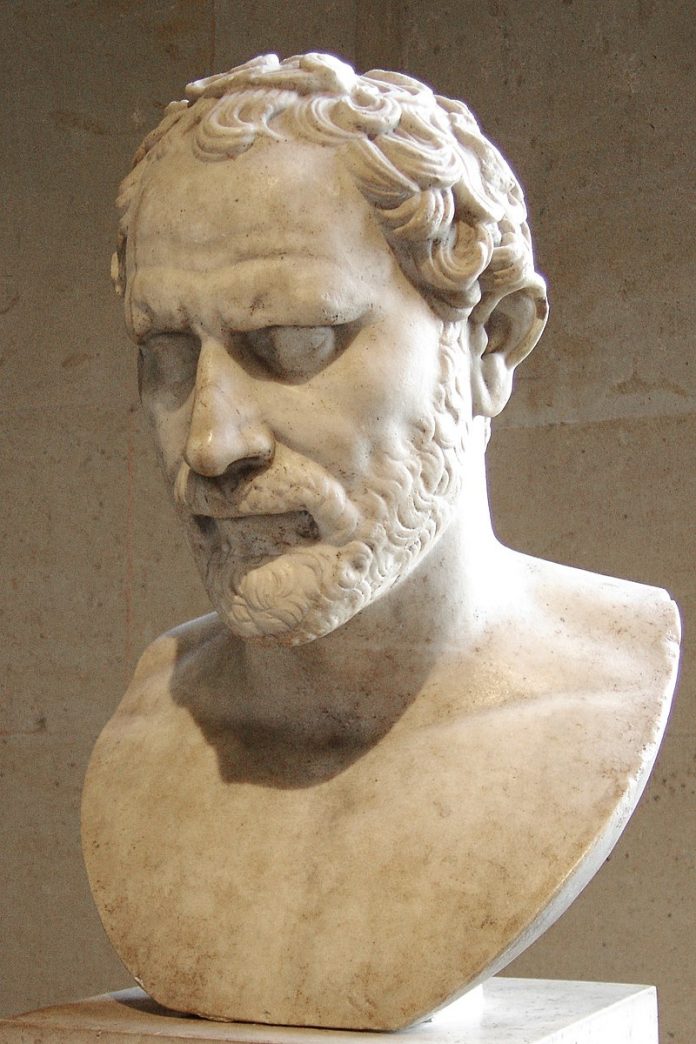

The words that open this article were spoken by the great Athenian statesman Demosthenes in 351 BCE: 2,370 years ago. It was in a speech about Liberty, the very foundational principle of America. Demosthenes warned against “the spectre of Athenian politicians who are ideologically opposed to the democracy,” according to Dr. Guy Westwood at the University of Oxford in his new book about Demosthenes and his rival Aeschines.

Westwood looks closely at the power of rhetoric in shaping Athenian politics, and while he does not draw parallels with modern events, the analogues are starkly clear to anyone who reads this densely argued and insightful book. The birthplace of democracy is in ruins: you can see it for yourself on a visit to the Athenian Acropolis. If a certain oligarch continues his rampage against truth and democracy, how many years will remain before tourists visit the ruins of what Ronald Reagan called “the shining city on a hill?”

The analogues I mentioned become mirrors as Westwood opens the book by describing the role of statues in civic life. “Given that statues acted as vivid visual clues for recalling notable individuals and details about them, we find them becoming especially malleable forms of memorialization for orators’ purposes.” Statues erected to those who achieved fame in Athens became objects of contention, much like the Confederate statues whose widespread removal in the past year caused such an uproar in the body politic of America. One lawyer in Athens “sought to mobilize jury hostility against the defendant by casting him as a traitor to his own father’s statue in the temple of Zeus.” Demosthenes pointed out a statue to the recently deceased Iphicrates, in order to remind his listeners in court that Iphicrates “turned his back on his city” to serve others. Once again, human nature remains constant.

We saw in the Impeachment hearings, when Constitutional law professors testified, “the potential historical material had to move audiences made it susceptible to use by orators.” This quote comes not from commentary surrounding Impeachment, but rather Westwood’s explanation of how historical precedent was used by orators in Athens. Responding to his rival’s wanton misuse of history, “Demosthenes spins this as a totally irresponsible use of rhetoric by Aeschines in front of an audience who were not used to clever speeches, but it neatly demonstrates that in the right performance context, history really could be power.”

The wielding of that power – for good or evil – is the central pivot of this book, and the fulcrum upon which America will either be forged anew by the aptly-named Democrats, or broken by a party that has repudiated all sense of morality and decency to worship at the feet of a grotesque and despicable oligarch.

Demosthenes used all his vast knowledge of Athenian history for the good of the state. As the author states “Demosthenes’ construction of the Athenian past was a continuum from which examples may be drawn which resemble one another, because, whereas Athens’s substance is unchanging, the factors affecting the city’s success – the accidentals – form patterns which can be traced along that continuum.” Will this “accidental” presidency be merely a temporary defeat along a continuum, or will it represent a breaking point of civilization itself?

Faced with the threat of overturning the democracy, I will let Demosthenes have the last word as to what confronts every voting American now: Democracy or dictatorship, patriotism or treason against your father and forefathers who built the country:

“Many, many times, men of Athens, you have not been instructed as to what is the right decision but have been misled by shouting, intimidation, and lack of scruples on the part of orators. Do not let this happen to you today: it is beneath your dignity. Instead, make the right decision.”

The Rhetoric of the Past in Demosthenes and Aeschines: Oratory, History, and Politics in Classical Athens is $115 from Oxford University Press. I highly recommend this book, quite aside from its ability to reflect modern politics. Complete with a 46-page bibliography, it is the finest and most detailed study of trial cases in Classical Athens, and will appeal not only to Classical but legal scholars.