How the classical writings of ancient Greece and Rome were infused into Renaissance thought is the topic of this eminently fascinating book, edited by Syrithe Pugh at the University of Aberdeen.

Perhaps my favourite phrase in the book comes from an analysis of Samson Agonistes by Milton. Helen Lynch, also at Aberdeen, writes of “the thunderous synaesthesia of divine language” to describe what lands on the heads of the Philistines as Samson brings the temple down on them.

The book consists of a 30-page introduction by the Editor, followed by five chapters, of which the Editor wrote one. Its origin was a symposium at Aberdeen in 2015, which brought together specialists in both Classics and the Renaissance to discuss “the practice of allusion, imitation and intertextuality in poetry of both periods.” The result is like those miniatures that Renaissance princes enjoyed collecting – something that can be endlessly admired, in this case from an intellectual stance. Each chapter has copious footnotes (more than 120 in one case), with an 18-page bibliography to conclude the volume. There is much to unpack here so I will be selective.

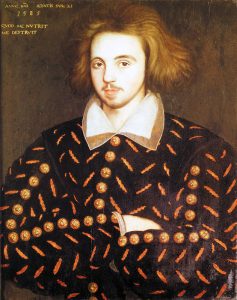

Emma Buckley (St. Andrews University) writes of how the work of the Roman poet Lucan (who died at age 25 in 65 CE) was revived by Christopher Marlowe (who died age 29 in 1593). Strangely linked (“a kinship of rare closeness” in the words of scholar J.B. Steane) by very short lives, each wrote major works. For Lucan it was Pharsalia (also known as Civil War), for Marlowe it was Tamburlaine. In his translation of Pharsalia from Latin to English, Marlowe “infuses the text with a different kind of energy by incorporating a cluster of self-quotation of his own previous work.”

In Pharsalia, a key image was “dextra,” which is right hand. It was this hand that Caesar extended to Pompey to guarantee kinship via marriage, but it turned into suicidal slaughter in Rome as the factions of each leader turned on one another. To understand fully Marlowe’s translation of dextra, one must read not only Buckley’s main text but her footnotes too. In the first instance Marlowe “hyperbolizes the suicidal right hand of the Roman people” by reimagining it as “an intoxicating , barbarous blood-thirst.” But when Lucan revives the imagery of dextra later in the poem, Marlowe “chooses to avoid these images.” One can see that from a comparison of the relevant lines by Marlowe and Thomas May a few decades hence (more on him later). May wrote “With what bloods losse, which civil hands had drawne?” Marlow translated the same line as “Might they have won whom civil broiles have slain.” Here hands become broiles. Going beyond what previous scholars have discerned, Buckley insists “Marlowe reanimates Lucan with his own literary life-blood, transfusing Marlovian imagery of blood and the sword with the imagery already to be found in Civil War.” Buckley elevates “the notion of literal blood-transfusion” to one of the figures Marlowe used for translation. One effect of this is to make Julius Caesar even “more dynamic and impressive” than Lucan portrayed him.

The impact of Marlowe’s translation was literally a thunderclap in the world of Elizabethan poetry. “The most unsettling exploration of the consequences of Marlowe’s remodelling comes in the anonymously authored academic drama The Tragedie of Caesar and Pompey.” It was composed in the 1590s and first published in 1606. Buckely looks closely at this little-known play which adopts the hyperbolizing approach of Marlowe to characters ranging from Caesar and Cleopatra to Brutus himself. It leads to the most dramatic possible final act, where “Discord emerges again to anticipate Brutus’ downfall, predict the dire cosmological phenomenon of the sun’s eclipse and finally invite the dissolution of the boundaries between hell and earth.” Wow! Buckley writes the author of the play “exploits to the hilt the amoral potential of a Tamburlanian Caesar inhabiting a Lucanian world, transforming the story of Rome into a full-on revenge tragedy.” As students of history will recall, Lucan committed suicide as a result of his treasonous activity against the state (too bad the former Dictator of the United States has not read Lucan for the manly way out). Since he died so young, Lucan did not finish Pharsalia; this was left to Thomas May in the 1630s and 1640s. In a strange twist of fate, May also became a traitor to the English Crown – even though he did not commit suicide, his body was later dug up and thrown into a pit after the Monarchy was restored in 1660. May wrote the conclusion of Pharsalia with a heavy dose of Marlowe-flavoured boldness. “May’s Continuations,” writes Buckley, “bring to a fitting close the programmatic blood-trope first encoded by Marlowe and then exploited by the exuberant author of Caesar’s Revenge.” This exploration of the intertextuality of a classic poem with its Renaissance counterparts is both superb and utterly convincing. Anyone who regards ‘reception history’ as a bit dull should read this.

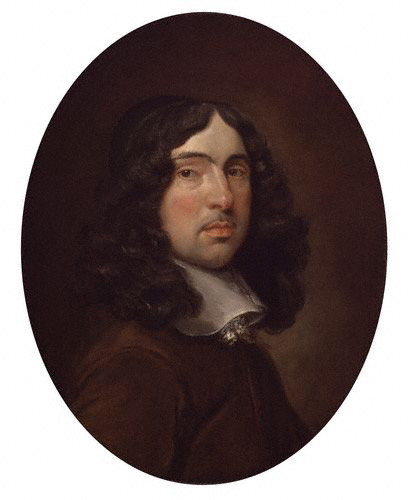

Another compelling chapter is written by Stephen Hinds (University of Washington, Seattle). He looks at the work of Andrew Marvell (1621-1678), who enjoyed writing Latin poetry in the actual words of Horace. He advanced to writing the same poem in both Latin and English. In On a Drop of Dew, Hinds discerns the Latin poem actually “drives the agenda of its English twin.” He tantalizes us with the more synoptic view that “there are moments when the English poem seems to seize a broader conceptual initiative from the Latin,” where the Roman imagery is transformed into “something newer, more distinctive,” but unfortunately he takes this no further.

Hinds rightly takes a swipe at the modern reference work Cambridge Companion to Marvell: “it is hard, indeed, to find two consecutive sentences of any of Marvell’s Latin poetry.” Since Marvell’s English poetry “would not be what it is without its Latin twin,” this chapter addresses an issue that extends to Milton who often wrote “in a Virgilian way.” It leads Hinds to set out an important agenda for future research: “This could be the start of a much larger conversation about questions of linguistic hierarchy, about the hazards of intertextual strait-jackets, and about the arguably greater ability of the vernacular – as opposed to Latin – to facilitate a more open kind of epic intertext.”

Scholars have long wondered why four stanzas of Marvell’s poem The Garden has no corresponding Latin text. Hinds takes a bold approach “to the ‘finding’ of the Latin poem in the English-only stanzas.” One example he gives is translating apple, nectarine, peach and melon into Latin. They all become one undifferentiated word: malum. The author then poses a pregnant question: “Is there perhaps a linguistic joke about a profusion of fruit so unprecedented that it is beyond the resources of the Latin language to give it expression?… One of the joys of early modern Latin is that it comes so multiply and deeply embedded in its own time.” Such is the word orient, referring to the Near East and India, “whose contemporary usage in the seventeenth century was historically unavailable to its Latin ancestor oriens.” The discussion in this 34-page chapter is both wide-ranging and deep. As Hinds himself states, there is at work a kind of “diplomatic passport that guarantees free movement for poets and readers across frontiers of space and time.” As Pugh writes in her Introduction, “good poetry is immortal.” Just imagine an incarnation of Dr. Who that delights in spouting poetry!

I have no space (pun intended) here to consider the marvellous insights of Philip Hardie (University of Cambridge) on his provocatively-titled chapter Flying with the immortals: reaching for the sky in classical and Renaissance poetics. Suffice it to say his work will be referenced in my own research papers on poetry in the context of historical astronomy. Overall, a very fine and important book that will have broad relevance and appeal to scholars in several disciplines.

Conversations: Classical & Renaissance intertextuality is $120 from University of Manchester Press