The Black Bottom and Paradise were two intertwined predominantly black enclaves situated in the city of Detroit. The area was bounded by Brush Street on the west, Grand Trunk R/R tracks on the east bisected by Gratiot Avenue. The “sepia community’s” heyday was in the 30s, 40s and 50s: a city within a city.

Detroit at the time being predominantly white, the Black Bottom was a place for blacks to thrive and do their financial business. It was where jazz bands and blues emanated nightly.

Many of the blacks who came up from the South to find riches in the auto factories made the Black Bottom their home.

Having been raised in the “hood” in the far west side, I remember when I-75, I-375 and the Ford Expressway were deliberately planned to plow through this area. It was for the purpose to consciously destroy it in the name of urban renewal. Bulldozers ravaged the Black Bottom out of existence with all its history and culture cast asunder. As the highway was extended north it also displaced a substantial white population, but they were able to move into other white-only areas. The blacks were not given any housing assistance that they were promised, and so were scattered.

By the early 60s, 432 residences, 104 businesses and 22 manufacturing plants in the area had been decimated, with its residents scattered to the wind.

Through a series of compilation vignettes, the author of this novel, Alice Randall (a Detroit native), employs a narrator (Ziggy Johnson, writer for the black newspaper Detroit Chronicle) to spin the intrigue on this unique area. Using his columns as a source and applying fictional literary leeway, the author paints a vivid picture of the Black Bottom.

Through the vignettes of black Detroiters, and their struggles, such notables as Sammy Davis, Billy Eckstein, Nat King Cole, Charles Diggs, Ethel Waters, Martin Luther King appear with their legacies entwined.

In each vignette, the person who is considered is canonized as a saint, as represented by the title of the book “Black Bottom Saints”. And in doing so, the author uniquely creates a recipe for a drink for each saint to celebrate their uniqueness. Concocting these libations is certainly a twist at the end of each chapter.

At times the text reads like a “stream of consciousness,” which can be difficult to grasp. Also, more details are needed on the Black Bottom characters. To fully understand this novel, one must be in the 65+ set, with some personal recollection of the era and the real-life stars (already mentioned) and other characters. Remember the Martha Raye show on TV from 1954 to 1958? If not, you may be too young for this novel.

In conclusion, today Detroit has proposed to plow under the I-375 Expressway, to try and rectify the wrongs that have been done to the black community. Too little, too late, but in retrospect Detroiters are trying to appease their conscience of part wrong-doings.

The indelible image of the Black Bottom community- “walking tall, fist balled, brain firing on all cylinders; folks who have steel in their spines, in their jaws and in their will” – will endure, even though the Black Bottom is no longer a place but is now only a state of mind.

Alice Randall is Professor at Vanderbilt University.

Black Bottom Saints is by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Book Review written by M. Emanuele

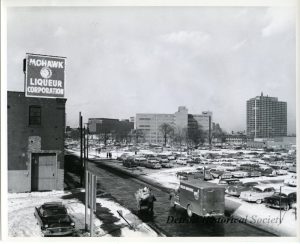

Photo of Black Bottom: A view along Hastings Street, looking north from E Lafayette Street. To the left is the Mohawk Liqueur Corporation. To the right is a large parking lot full of cars. In the background are the Stroh Brewery, Wayne State University School of Medicine, and The Pavilion. Dated Jan 5, 1959.

Hastings Street, which ran north-south through Black Bottom, had been a center of Eastern European Jewish settlement before World War I, but by the 1950s, migration transformed the strip into one of the city’s major African-American communities of black-owned business, social institutions and night clubs. It became nationally famous for its music scene: major blues singers, big bands, and jazz artists—such as Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstine, Pearl Bailey, Ella Fitzgerald, and Count Basie—regularly performed in the bars and clubs of Paradise Valley entertainment district. It is also where Aretha Franklin’s father, the Reverend C. L. Franklin first opened his New Bethel Baptist Church on Hastings Street.

Photo by Art Greenway. Photo & text courtesy of Detroit Historical Society.