This book on the cultural remains of the English Civil War has many strengths and a notable weakness.

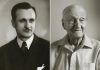

The text is by Dr. Stephen Bann, emeritus professor of History of Art at the University of Bristol. While the book has many elements (including memorials that can be found in churches throughout the country), the two dominating ones relate to the bronze statue of King Charles I in London, and paintings relating to the King and the man most responsible for his death in 1649, Oliver Cromwell (an example of evil incarnate who should never have been born).

Bann does a superb job at placing the statue of the King in context, beginning with a small print by an unknown artist from 1645, showing the monarch on horseback. Underneath the image are four lines, beginning with “Return, in Peace, Great Charles, redress our woes.” The king had left London in 1642, raising his standard against the forces of Parliament. Bann states “the symbolism, and perhaps the sentiment, is certainly not very far from the verses that the young poet John Milton had been writing in the early years of Charles I’s reign.” It marks a moment in time when reconciliation was earnestly wished for, entreating Charles to return to the capital to quell the woes of the kingdom.

“The most significant aspect of the print is,” Bann writes, “the fact that the absent king is shown mounted on horseback.” He notes the recent precedent set for this depiction was a series of prints 30 years earlier for Charles’ father, King James. Charles himself figured in the series. “It is a fragile artefact, but no doubt bears an authentic message, from a period when such a plea might not have been altogether unrealistic.” Twenty-one years after Charles left London, his statue on horseback was placed at Charing Cross; and it has been on its present site since 1675. It has survived every disaster, including the Glorious Revolution and two World Wars. Bann charts its fascinating history through literature, art and poetry, noting along the way other horseback sculptures of royalty on the Continent which have either been destroyed or moved. Charles I rides on.

The depiction of Charles I and Cromwell in 19th century art is where the book runs into rough waters. It was during this period, three centuries after the Civil War, that artists really tried to engage psychologically with the trauma that the execution of the King created. While the author offers a fine analysis of much of this period, it goes off the rails (to use another metaphor) in the paintings of Paul Delaroche and Eugene Delacroix.

First, the colour reproduction of the 1831 Delaroche work, Cromwell and Charles I, does not do justice to the painting. Much of the detail is lost in a muddied cast over the work, and even the vibrant red upholstery of the chairs upon which rests the coffin and body of the King looks dull brown. This, of course, is the fault of the publisher.

Curiously, the French seemed more fascinated than the English by the interaction between Charles and Cromwell. Bann relates the remarkable bit of background that Delaroche “began the work by composing a three-dimensional model of the scene in miniature, and in that process shaped a tiny head of Charles I, which was later cast in bronze.” What Bann does not state is the public ridicule occasioned by the painting in later years (the magazine Punch, which was read by nearly everyone, published a parody of it in 1852, casting the King of the French, Louis Napoleon, in the role of Cromwell, gazing at the Corpse of Liberty!). While he does delve into the very negative reaction of Delacroix to the painting, the result – which was his own watercolour – is not depicted here. I found that quite astonishing. We are shown instead (covering a full page) a Delacroix work from 1828, Cromwell at Windsor Castle. This is certainly relevant to the overall analysis of Charles-Cromwell works, but why then does it appear in the midst of the Delaroche discussion? Even more amazing: the name of Delacroix not even appear in the Index!!

It must be said that the following chapter, entirely devoted to the Delaroche painting Charles I Insulted by the Soldiers of Cromwell, is a tour de force of artistic analysis. This is due in large part to the fact Bann was present 11 years ago in a “remarkable ceremony in the drawing room of a Scottish country house” where the canvas of the painting was unrolled in the presence of “specialists from the National Galleries of Edinburgh and London.” It had suffered damage in WW II, and was sent from London to Scotland to prevent further damage. Thus, after being in seclusion for 70 years, it was first seen by the public in 2010 at the National Gallery in London along with another work by Delaroche. Bann’s study of how this remarkable painting came to be, including being iconographically linked with previous depictions of the ‘mocking of Christ’, is most fascinating. He even traces the idea of a puff of smoke being blown into the face of the king as he sat pensively holding a book, surrounded by Cromwell’s goons.

The iconography of subsequent paintings of Cromwell (especially the absurd work 1874 by Ford Madox Brown of Cromwell at his Farm) shows just how far some 19th century painters were willing to go in order to ‘humanise’ Cromwell.

Despite the mis-step with Delaroche and Delacroix, this is a very fine book that, for the first time, elucidates the scenes and traces left by the Civil War on the psyche of Europe, especially that of England and France.

The book concludes with a 4-page Chronology, 17 pages of References, a 5-page Bibliography, and a 9-page Index.

There are a few typos: pg. 153 references illustration 72, when 71 is meant; pg. 187: laiden should be laden; pg. 199: ‘a visit the Musee’ should be ‘a visit to the Musee’.

Scenes and Traces of the English Civil War (288 pgs) is $60 from Reaktion Books in the UK (distributed in the US by the Univ. of Chicago Press)