It may not be a unique event, but certainly the premiere of a choral work for symphony orchestra in the Esperanto language is a great rarity. To have such a work written in an obscure field of music must, however, be quite unique. Tucson audiences experienced this delight at the latest offering of the Tucson Symphony Orchestra.

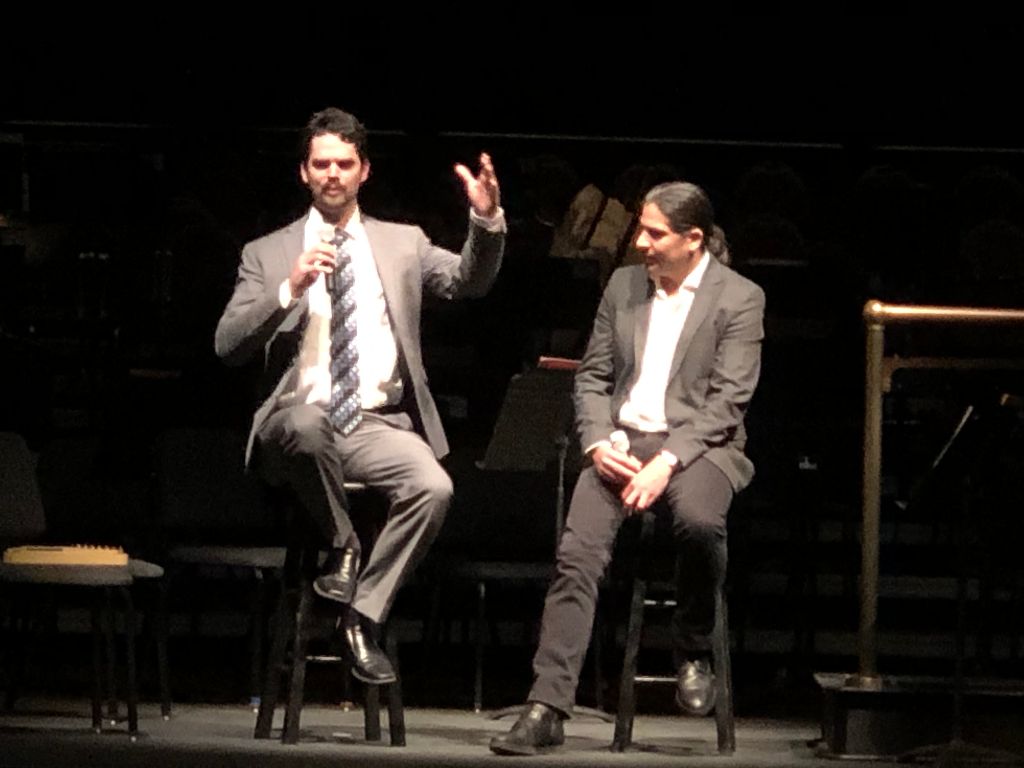

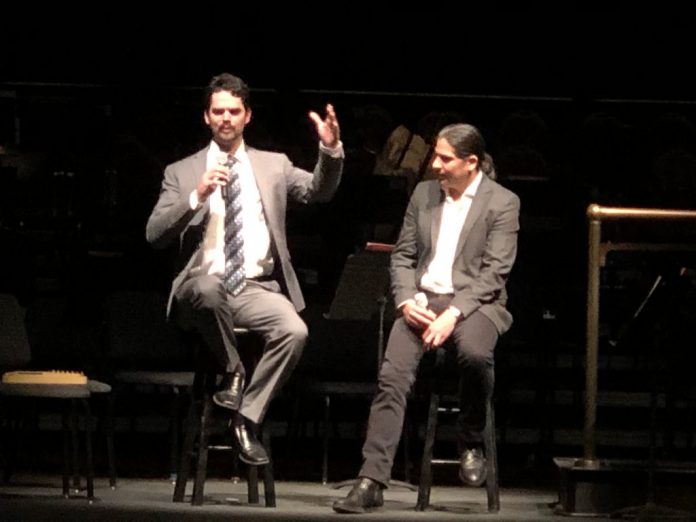

Composer Robert Lopez-Hanshaw was on hand to explain his work to the patrons at the Tucson Music Hall on January 24. Formerly with the Young Composers program hosted by the TSO, he has since become a general music teacher with a keen interest in the history of music. For this work he employs microtonality, where he is able to employ “pitches that exist outside the possibilities of the piano keyboard. I divide the octaves into 72 tones each, which allows for accurate harmonies. My composition has a connection with another piece on the program, Resphigi’s Church Windows, which uses a scale employed in Greek Orthodox chant and hymns to Apollo that use the 72-tone scale.”

The composer first encountered Resphigi’s composition when he was driving home from high school. “I heard it in a classical radio station and was so moved by it. It didn’t use harmonies I was used to, it uses expressionistic harmonies.”

For the choral portion, Lopez-Hanshaw turned to a 1951 poem by William Auld, written in Esperanto. “The poem is about yearning to connect. The music that I have written encompasses both familiarity and distance, so it has a certain tension.” The poem is all about the vast cosmos and stars. The composer told me in an exclusive interview “Thinking about the vast distances between the stars played a part in my work.”

In addition to using melodies from an ancient Greek scale termed the enharmonic mode, the composer employs the same symbol in his notation that Giuseppe Tartini created to indicate a 1/6th tone. Tartini (1692-1770) “was a music theorist who dealt with perfect harmonies,” his most famous composition being the Devil’s Trill Sonata, the origins of which were related in a book by the famous French astronomer Jerome Lalande (1732-1807).

The 10-minute composition Vokas Animo by Lopez-Hanshaw gives prominence to an instrument the rarely gets its due: the harp is clearly heard at the beginning and the exceptionally dramatic conclusion. As the counter-textual link between the orchestra and the choir, it’s role is central.

Local music expert Conlan Salgado tole me the music possessed a greater expression than music based on the normal 12-tone scale because of the precision of the quarter tones. “The best way to listen to the piece was to treat the music itself as a stream, and let it wash over one. There was also something that, because of the small intervals of the quarter tone, was never quite distinct about the melodies.”

This was followed by Church Windows, which was premiered in 1927 in Boston. It consists of four preludes based on Gregorian chants. The experience of listening to this is like gradually opening a cloisonné enamel case by Faberge – an experience of sheer delight engendered by intricacy and beauty. The ever softer notes that conclude the first prelude are in stark contrast to the whirlwind that opens the second. Once the storm passes we feel a gentle breeze and a few rays of sunshine. At the conclusion, heralded by brilliant brass fanfares, we are bathed in glorious sunshine filtered through those church windows. In the third we are given a closer look at the stained glass windows with chromatic tones of the orchestra highlighting each colour in turn. The final prelude blossoms into a loud evocation of joy, given voice by organ music, which is also rarely heard in a symphony concert.

The second portion of the TSO concert featured soprano Federica Lombardi in three compositions by Rossini, and a Rossini-inspired piece by Resphigi entitled Rossiniana. This formal operatic composition relies on the ability of the soprano to project the joie de vivre with which Resphigi infused his interpretation of four piano pieces by Rossini called Sins of My Old Age. Lombardi rose to the challenge, delivering this to perfection.

Backed up by both the TSO and the Tuscon Symphony Chorus, the conclusion of the concert with Rossini’s Stabat Mater (premiered in 1842) began with a solemnity that could not have been a greater contrast with Rossiniana. Dreamy notes from the harp are only ended by the striking of the gong to wake one from a lovely daydream. The horns then herald the soprano and an emphatic invocation from the chorus to a glorious conclusion befitting one of TSO’s finest musical offerings, an inspired selection by conductor Jose Luis Gomez.

Visit the website for tickets to future concerts: tucsonsymphony.org