“All art constantly aspires to the condition of music.” So said the literary and art critic Walter Pater in 1888. But according to Beethoven, his 6th Symphony is “more an expression of feeling than painting.” Only by examining the origins of the symphony from a source other than art can we appreciate that feeling properly.

The Tucson Symphony Orchestra offered a double header of Beethoven symphonies in its latest tribute to the classical music master on his 250th birthday. They also performed his first symphony on Feb. 14 and 16, but in this review I will concentrate on the 6th.

TSO music director Jose Luis Gomez said the 6th “precedes symbolism,” and I find evidence of that in 1886 when the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé gave voice to the very impulse that led Beethoven to create the 6th Symphony 78 years earlier. “I say: a flower! And out of the oblivion to which my voice relegates every contour: up there rises musically an idea riotous or lofty.” In the case of this pastoral symphony it is most definitely lofty, not riotous.

Beethoven certainly had flowers on his mind in 1808, for the 6th Symphony (Op. 68) was premiered the same night his Choral Fantasy (Op. 80) was performed in the famous 4-hour concert in Vienna on Dec. 22 that year. In the Choral Fantasy (Performed by True Concord in Tucson on Feb. 22, 2020), Beethoven wrote about flowers explicitly in words sung by the chorus:

Graceful, charming and sweet is the sound

Of our life’s harmonies,

and from a sense of beauty arise

Flowers which eternally bloom.

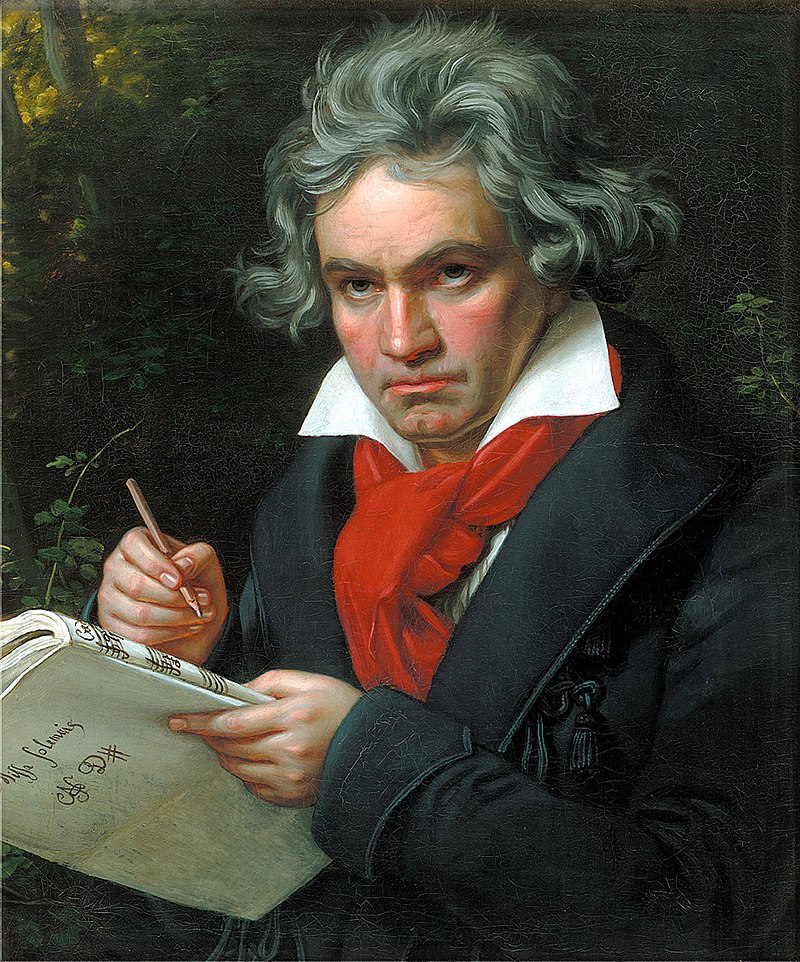

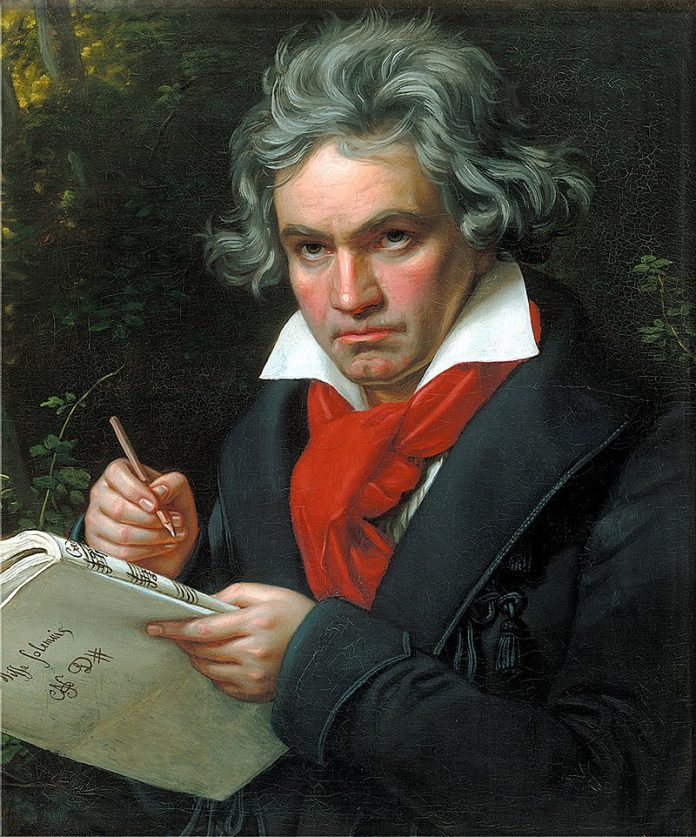

One of Beethoven’s favorite books was Christoph Christian Sturm’s Reflections on the Works of God in the Realm of Nature, from the 1780s, a compendium of daily homilies including reflections on the stars, planets and even their moons. One immediately gets a sense of how Beethoven related to Nature by looking at his portrait against a leafy and wooded backdrop. He derived inspiration from Sturm’s work in writing some of his compositions, including the 6th Symphony. Here is a passage from Sturm that appears particularly relevant to the 6th, at a time when the hardship of deafness was setting in on his own pilgrimage of life:

Wheresoever we walk, flowers spring up beneath our feet, the fragrance

and beauties of which are destined to soothe and alleviate the hardships

attendant on the pilgrimage of life. The same regular succession is

observed in the human race as in plants and flowers.

Sturm also wrote “The nightingale is a musician of the first order among the inhabitants of the groves”. Thus it is no surprise to see that premiere musician of birds making an appearance in the 6th Symphony. In the second movement, the flute is the nightingale, the oboe is the quail, and the two clarinets are the cuckoo.

Gomez kept a tight rein on the pacing of the 6th through a series of rapid transitions that swept one along in an ever bolder evocation of Nature’s wonders. “The sixth was played in a faster interpretation than other recordings I have heard,” said local music expert Conlan Salgado, “so that may have made it more difficult for the instrumentalists. Yet I think that it was a finely crafted symphonic experience, and I appreciated how Gomez decided to highlight the dialogue of the woodwinds behind the strings.”

Once again Tucson was treated to a superb concert by its Symphony Orchestra. On Feb. 28, 29 and March 1 the TSO performs Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 at Catalina Foothills High School. Visit the website for tickets: www.tucsonsymphony.org